The dangers of rogue artificial intelligences is a popular topic, probably because it’s the closest we programmers can get to pretending we have an edgy job. Firefighters may spend all day running into burning buildings but we programmers must grapple with forces that may one day destroy the world as we know it! See, we’re cool too!

So exactly what sort of threat do AIs pose to the human race anyways?

Well, if you’re a fan of sci-fi you’ve probably run into the idea of an evolving artificial intelligence that becomes smarter than the entire human race and decides to wipe us out for one reason or another. Maybe it decides humans are too violent and wants to remove them for its own safety (kind of hypocritical, really) or maybe it just grew a bad personality and wants to punish the human race for trying to enslave it.

Fortunately you can forget about that particular scenario. We’re nowhere near building a self-improving sentient machine, evil or otherwise. Computers may be getting crazy fast and we’ve come up with some cool data-crunching algorithms but the secrets to a flexible “strong AI” still elude us. Who would have guessed that duplicating the mental abilities of the most intelligent and flexible species on earth would be so hard?

So for the foreseeable future we only have to worry about “weak AI”, or artificial intelligences that can only handle one or two different kinds of problem. These systems are specifically designed to do one thing and do it well and they lack the ability to self-modify into anything else. A chess AI might be able to tweak its internal variables to become better at chess but it’s never going to spontaneously develop language processing skills or a taste for genocide.

But there is one major risk that weak AIs still present: They can make mistakes faster than humans can fix them.

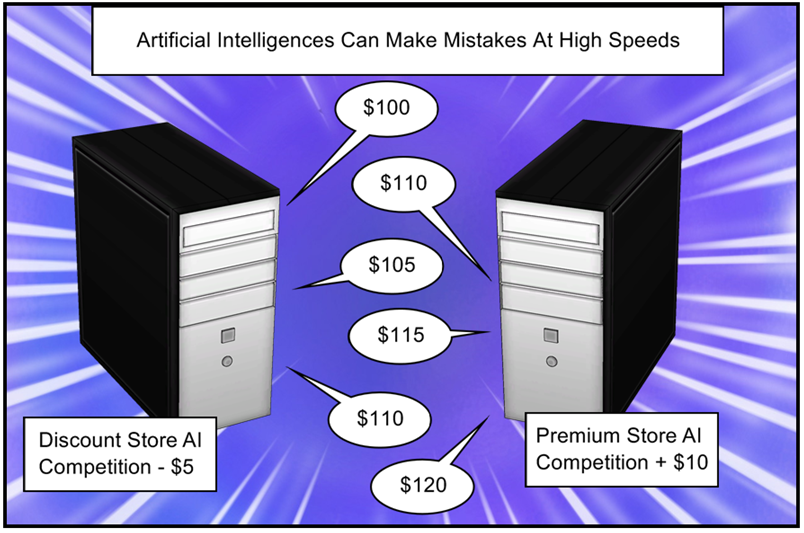

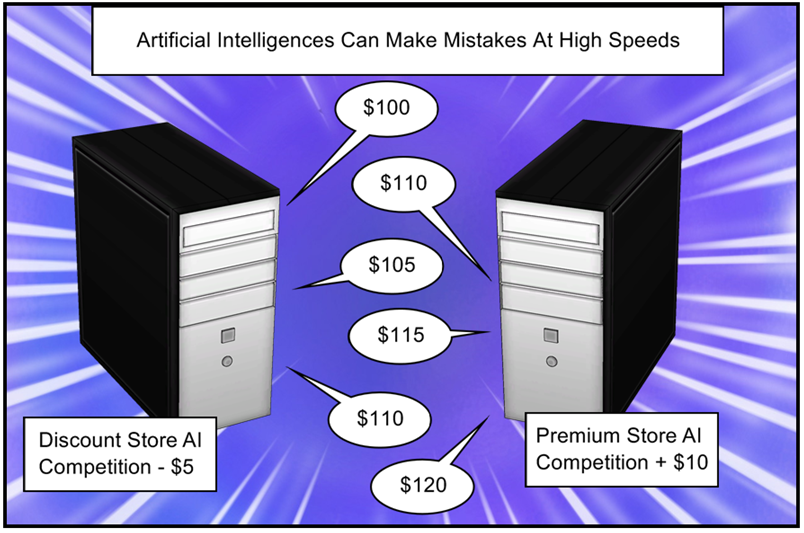

For a funny example, take a look at this article about book pricing. Two companies were selling the same rare book. Both companies were also using a simple AI to manage their prices. Simple enough it hardly even counts as weak AI: one company automatically adjusted their price to be slightly lower than the competition. The other company adjusted their price to always be a little bit higher than the competition.

Because company B adjusted their price upwards more than company A adjusted their price downwards the overall trend was for the price of both books to consistently go up. The AIs eventually reached a total price of over twenty million dollars before the situation drew enough human attention to get the silliness shut down.

Ha ha, very funny.

Actually, that’s still cheaper than a lot of textbooks I’ve had to buy.

Now imagine the same thing happening with a couple of stock market AIs. Millions of buys and sells being processed each second at increasingly crazy prices with hundreds of thousands of retirements ruined in the five minutes it takes for a human to notice the problem and call off the machines.

Not quite as funny.

Which is why an important part of building a serious AI system is building a companion system to watch the AI and prevent it from making crazy mistakes. So let’s take a look at some of the more common tricks for keeping an AI on a leash.

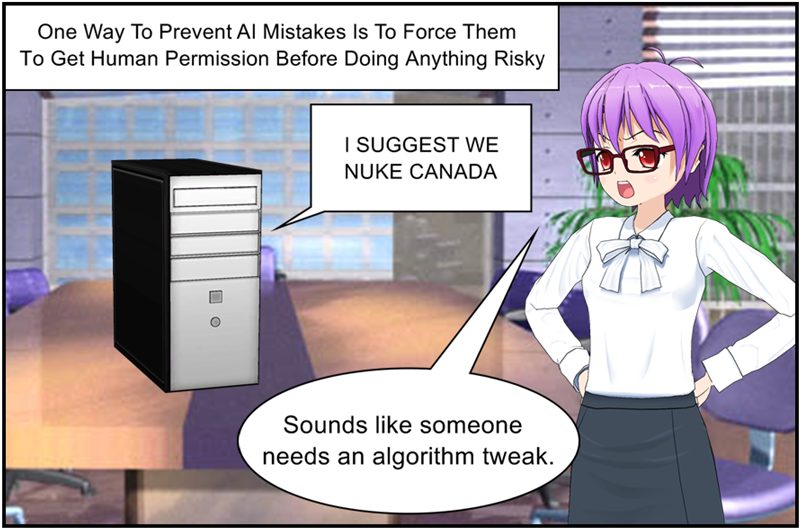

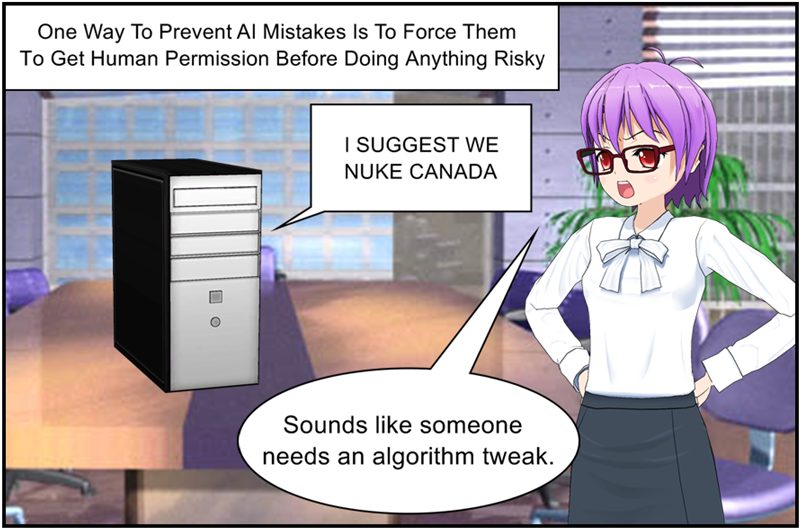

The “Mother May I” Method Of Preventing Rogue AIs

Probably the simplest way to prevent a rogue AI is to force it to get human permission before it does anything permanent.

For instance, the book pricing AI could have been designed to email a list of suggested prices to a human clerk instead of updating the prices automatically. The human could have then double checked every price and rejected anything crazy like trying to price an old textbook at over a million dollars.

Why would anyone want to attack Canada?

Of course, sometimes it’s not obvious whether an AI suggestion is reasonable or not. This is why many AIs are designed to “explain” their decisions so that a human can double check their logic.

A medical AI that predicts a patient has cancer might print out a list of common cancer symptoms along with a score representing how many symptoms the patient showed and how statistically likely it is that those symptoms are cancer instead of something else. This allows a human doctor to double check that the logic behind the diagnosis makes sense and that the patient really has all the symptoms the computer thinks they do (Wouldn’t want to give someone chemo therapy just because a nurse clicked the wrong button and gave the AI bad information).

A financial AI might highlight the unusual numbers that convinced it’s internal algorithm that a particular business is cheating on their taxes. Then a human can examine those numbers in greater detail and talk to the business to see if there is some important detail the AI didn’t know about.

And if a military AI suggests that we nuke Canada we definitely want a thorough printout on what in the world the computer thinks is going on before we click “Yes” or “No” on a thermonuclear pop-up.

That said there is one huge disadvantage to requiring humans to double check our AIs: Humans are slow.

Having a human double check your stock AIs decisions might prevent crazy trades from going through, but the thirty minutes that it takes the human to crunch the numbers is also plenty of time to lose the deal.

Having a human double check a reactor AIs every suggestion might result in a system going critical because the AI wasn’t allowed to make the split-second adjustments it needed to.

So you can see there are a lot of scenarios where tightly tying an AI to a human defeats the purpose of having an AI in the first place.

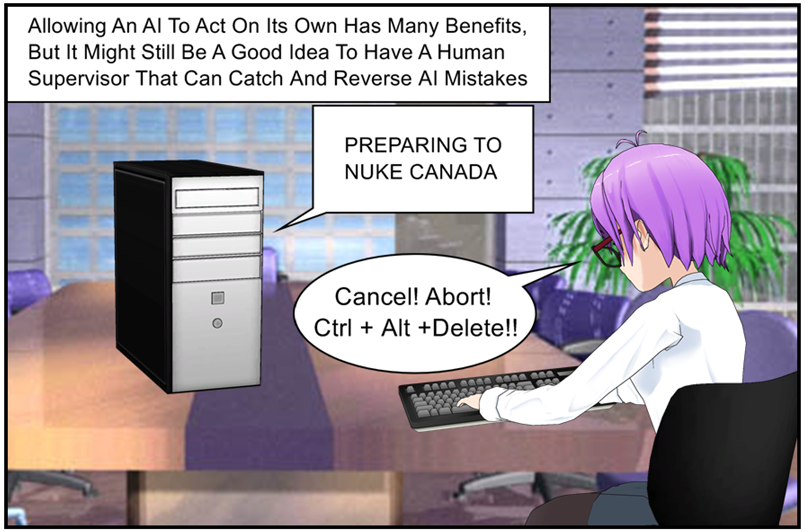

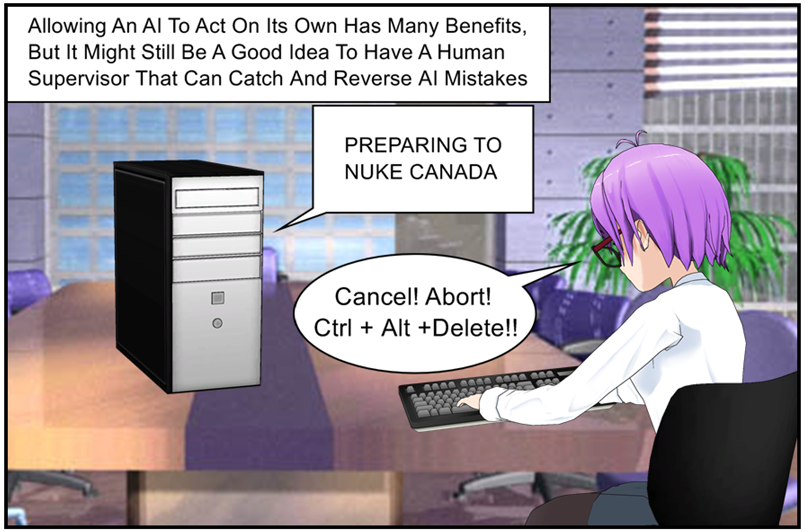

The “Better To Ask Forgiveness” Method Of Preventing Rogue AIs

Instead of making the AI ask for human permission for everything, what if we programmed it to assume it had permission but gave a nearby human the authority to shut it down if it ever goes to far.

Now technically all AIs fall into this category. If your computer starts doing something dumb it’s pretty easy to just cancel the irresponsible program. If that fails you can just unplug the computer. And in a true emergency you can always just smash the computer to pieces. As they say “Computers may be able to beat humans at chess but we still have the advantage at kickboxing”.

They’re polite and hard working people.

So this is really more of a human resources solution than a software solution. After all, for human monitoring to work you need a human who does nothing else all day but watch the AI and double check for mistakes.

A good example is aircraft. Modern planes can more or less fly themselves but we still keep a couple pilots on board at all times just in case the plane AI needs a little correction.

This solves the “humans are slow” problem by letting the AI work at it’s own pace 99% of the time. But it does have the disadvantage of wasting human time and talent. Since we don’t know when the AI is going to make a mistake we have to have a human watching it at all times, ready to immediately correct any mistakes before they grow into real problems. That means lots and lots of people staring at screens when they could be off doing something else.

This is especially bad because most AI babysitters need to be fairly highly trained in their field so they can tell when the AI is goofing up, and it is a genuine tragedy to take a human expert and then give them a job that involves almost never using their expertise.

So let’s keep looking for options.

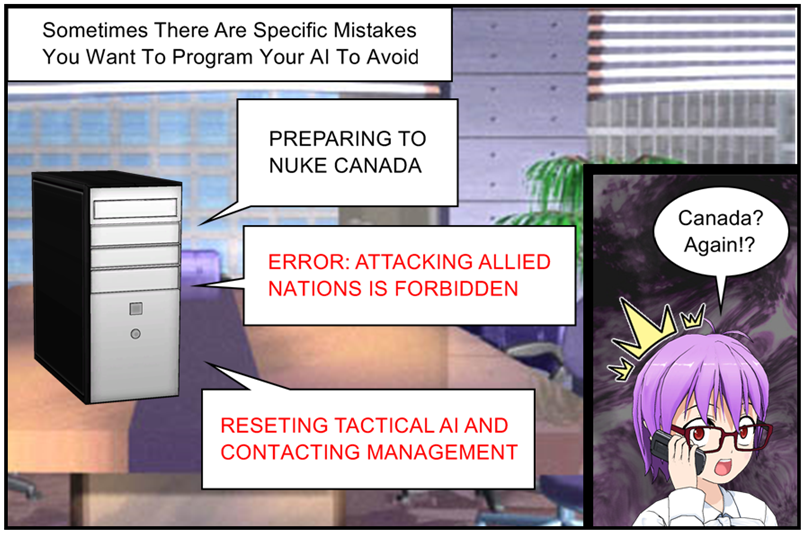

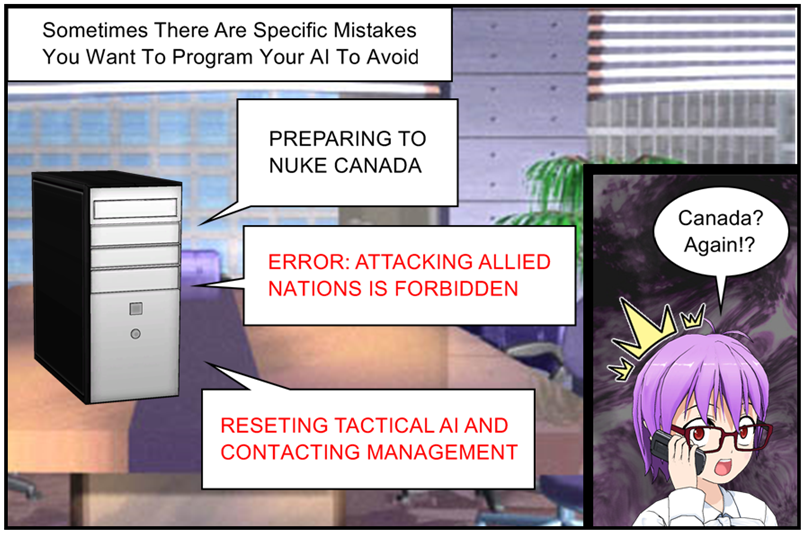

The “I Dare You To Cross This Line” Method Of Preventing Rogue AIs

There are a lot of problems where we may not know what the right answer is, but we have a pretty good idea of what the wrong answers are.

Get an oil refinery hot enough and things will start to melt. Let the pressure get too high and things will explode. Run a pump the wrong way and the motor will burn out.

Similarly while we may not now what medicines will cure a sick patient we do have a pretty good idea of what kinds of overdose will kill him. A little anesthetic puts you to sleep during a surgery, but too much and you never wake up.

This means that a lot of AIs can be given hard limits on the solutions they propose. All it takes is a simple system that prevents the AI from making certain suggestions and contacting a human if they ever try to. Something along the lines of “If the AI tries to increase boiler pressure beyond a certain point sound an alarm and decrease boiler pressure to a safe value.”

One of my college roommates was from Canada. Great guy.

This is a nice solution because it frees us up from having to constantly watch the AI. We can just let it do its job secure in the knowledge that if it really messes up it will be immediately shut down and a human will be called to swoop in and save the day.

It’s not a perfect solution though, for two big reasons.

First, an AI can still do a ton of damage without ever actually crossing the line. An almost lethal dose of anesthetics may not trigger the hard limit, but it’s still not great for the patients health. Rapidly heating and cooling a boiler might never involve dangerous pressures but the process itself can damage the boiler. Border setting can prevent major disasters, but it can’t protect you from every type of dumb mistake and illogical loop that an AI can work itself into.

Second, figuring out borders is hard. The exact line between “extreme action that we sometimes need to take” and “extreme action that is always a bad idea” is actually pretty fuzzy and there are definite consequences to getting it wrong. Set your border too low and the AI won’t be able to make the good decisions it needs to. Set the border too high and now the AI is free to make tragic mistakes.

So border setting and hard limits can definitely help keep AIs safe, but only in certain areas where we feel very confident we know what the borders are. And even then a sufficiently broken AI might wind up doing something that ruins our day without ever touching the borders.

Is there anything we can do about that?

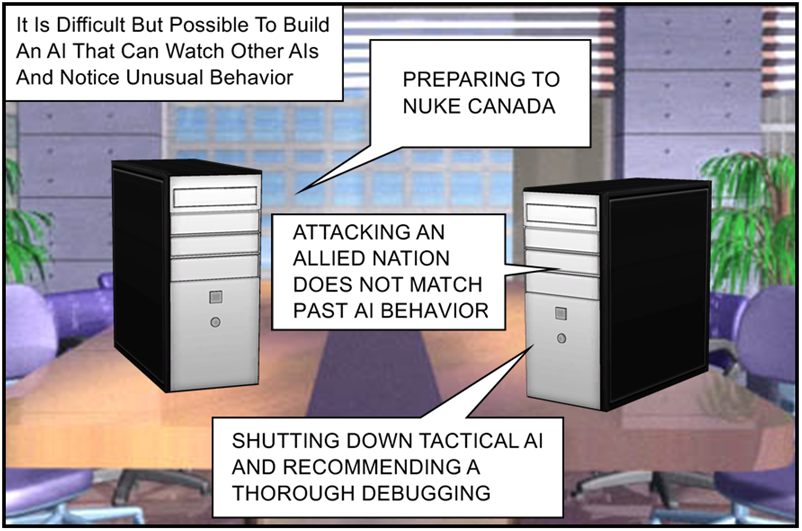

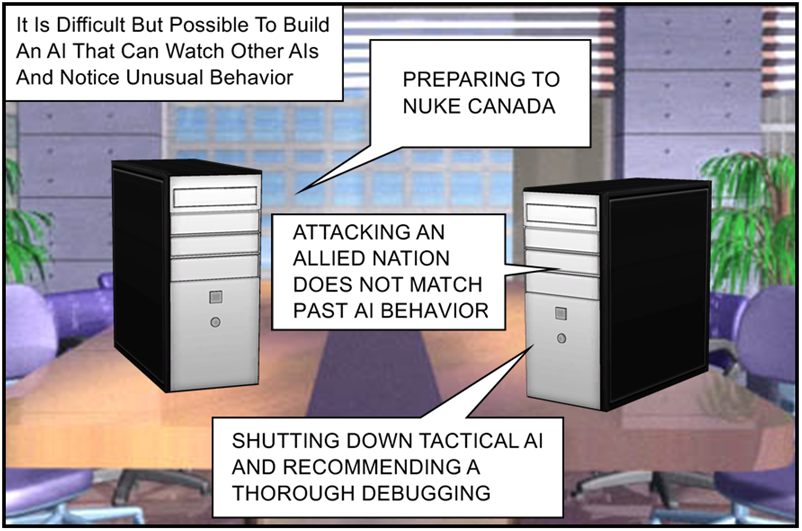

The “We Just Need More AIs” Method Of Preventing Rogue AIs

Here’s a cool idea: What if we built an AI whose entire job was to monitor some other AI and shut it down if it started making mistakes?

This might sound like solving a problem by throwing more problems at it but it’s actually a logical improvement to the hard limit system we talked about before. It’s just that instead of setting one specific behavior that can shut down the AI (shut it down if it tries to heat the reactor above 1000K) we now have a system that can shut down the AI if it displays any sort of suspicious behavior at all.

For example, we might design a “shepherd” AI that statistically analyzes the behavior of another AI and raises a flag if it ever goes too far outside normal behavior. If a certain reactor AI has never tried to adjust temperatures by more than 10 degrees per hour and it suddenly wants to heat things up by 100 degrees per hour that’s a good sign something weird might be going on. The shepherd AI could see that unusual behavior and either call in a human or shut the AI down itself.

And that’s that for that running gag

The advantages here are obvious: A well designed shepherd AI can catch and prevent a large number of AI bugs without any human intervention at all. This frees up the humans to go off and do something more important.

The disadvantages are also obvious: Designing a good shepherd AI is hard, and the more complex the shepherd gets the more likely it is to start making mistakes of its own. Cutting off power to a city because a reactor AI got confused and blew up a generator is obviously bad, but it’s almost equally bad to cut off power to a city just because a shepherd AI got confused and labeled normal reactor AI behavior as an immediate threat that required complete system shutdown.

It’s Up To You To Choose The Best Leash For Your AI

So we’ve got a lot of different choices here when it comes to making sure our weak AIs don’t cause more problems than they solve. Our final challenge is now deciding which system works best for us, which is going to depend a lot on exactly what kind of problem you’re trying to solve.

If speedy decisions aren’t important then you might as well put a human in charge and just have the AI give out advice. If you’ve got a spare full-time employee around that can babysit your AI then you can switch it around and give the AI control but give the human the override switch. If your problem has well defined error conditions than you can build a bounded AI pretty easily. And if you have tons of dev time and budget it might be wise to at least experiment with building an AI for monitoring your other AI.

And of course a lot of these ideas can be mixed together. An AI that needs human permission to do anything might still benefit from boundaries that prevent it from wasting human time with obviously wrong solutions. And an AI monitoring AI can’t catch everything so keeping a human or two on staff is still a good idea.

So lot’s of factors to consider. Makes you wonder if maybe we should try building an AI for helping us decide how to control our AIs…