Reinventing The Wheel

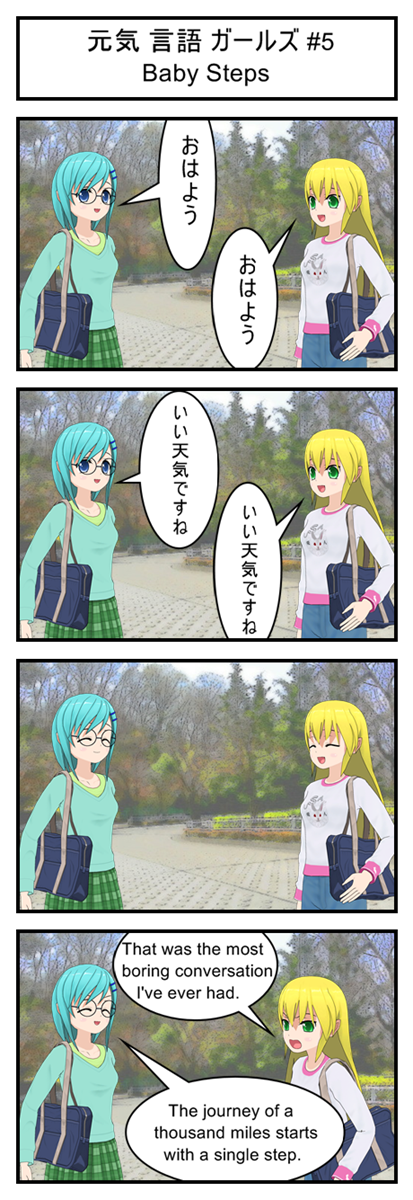

Let’s be honest: Building our own game engine from scratch is probably not a great idea. There are already open-source JavaScript game engines that do everything we need but better. If you need to quickly and efficiently build a bug free JavaScript game looking at one of these existing solutions would definitely be your first step.

But this is a Let’s Program! Doing things from scratch and learning the hard way is our goal.

Your Game Comes With The Following Pieces…

When you get right down to it, all games are made up of the following two things:

- Game Rules: How the game works.

- Game State: What is going on in the game right now.

This is true for board games, card games and videogames.

In a board game the rules are usually written on the back of the box and the game’s state is where the pieces are on the board. In a card game the rules usually come in a little pamphlet and the state is the cards in each person’s hand. In a videogame the rules are built into the code and the state is kept track of by computer variables.

Conceptionally there is no real difference between Bob and Sally playing checkers by reading the back of a box and moving pieces around a board and Bob and his computer playing Grand Theft Auto by reading millions of lines of code and moving bits of data around inside memory.

Sure, a video game like Grand Theft Auto has dozens of “turns” per second to simulate real time action, but behind the scenes it’s still just the same old board-game mechanic of “follow the rules”, “make your move”, “update where the pieces are”.

How To Play The Game

Now that we’re all on board with the ideas of game rules and game state we can simplify running a game to a process of three repeating steps:

- Check for player input

- Update the game state based on the game rules and the player input

- Redraw the screen based on the current game state

As an example, let’s imagine that the user presses the up key.

In step one the game checks for input and notices that the user has pressed the up key.

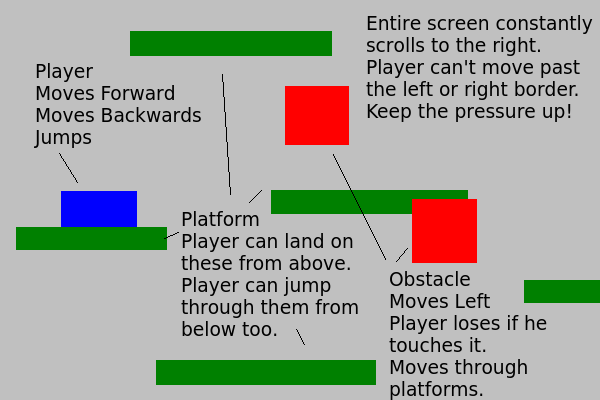

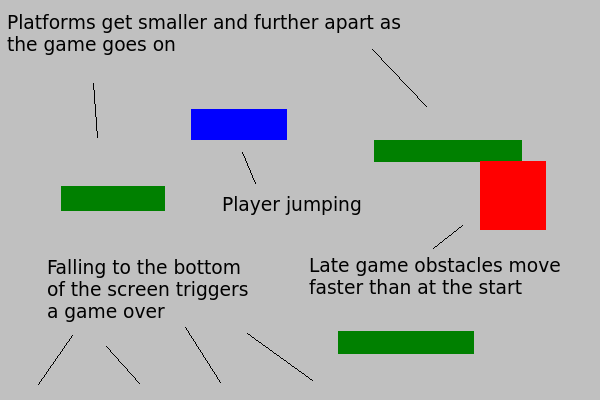

In step two it starts updating the game state. The game rules say that if the player presses the up key while standing on the ground he should “jump” by setting his up velocity to 20. The rules also say that the player and every enemy should move velocity pixels per update, so the game moves the player up 20 pixels and also moves two enemies on screen 10 pixels to the left. The rules also say the game should check for player/enemy collisions but the game doesn’t find any so it stops.

In step three the game now redraws the screen. It draws the player 20 pixels up in the air and draws the two enemies 10 pixels to the left of where they used to be.

50 milliseconds later the loop repeats.

In step one the game checks for input and notices that the user is still pressing the up key.

In step two the game checks the rules. The rules say that the up key only makes the player jump if he is standing on the ground, which he no longer is, so the input gets ignored. But the rules also say that characters in the air should have their velocity decreased by 5, so the player’s upward speed drops from 20 to 15. The game then updates all the characters, moving the player up by 15 pixels and the enemies left by 10. It checks for collisions and still doesn’t find any.

The game now redraws the screen. The player is now 35 pixels up in the air and the enemies are 20 pixels to the left of where they started.

50 milliseconds later the loop repeats a third time. And then a fourth time and a fifth time and so on.

Since the loop happens several dozen times a second the player gets the illusion that everything is happening in real time, but when you get right down to it the whole game could be converted into a turn-based boardgame no problem. Not that anyone would want to play a boardgame where it takes a few hundred turns to cross a room and the rulebook is written mostly in math terms… but the idea is still sound.

Looping In Javascript

Warning: We’re going to be experimenting with loops. Odds are good that you will make a mistake, create a crazy infinite loop, freeze your browser and have to force it to shut down. So don’t panic if your test page suddenly stops responding. Just close the browser and double check whatever code you just typed in.

Now our final goal for the game loop is to have it run once every 50 milliseconds. That’s 20 times a second, which is honestly a little on the low side for a video game but still high enough to feel like smooth-ish animation and interaction. Most importantly it’s slow enough that we can basically guarantee our code will complete inside of each loop, giving us plenty of wiggle room when prototyping messy code. After that’s done we can always go back and adjust the loop to run more often if the game feels too jerky.

Now the most obvious approach to make a loop run once every 50 milliseconds would be be to use “setInterval”, which allows us to schedule a function to repeat again and again every X milliseconds. It sounds perfect and this approach can work. I’ve used it in demo games before.

But running the algorithm once every 50 milliseconds does have one big issue: What happens if your function takes longer than 50 milliseconds? You can wind up in a situation where setInterval triggers a new game loop while the old one is still running, which is a bad bad thing. Having two functions trying to control your game at the same time can corrupt variables, double move characters and generally mess everything up.

To avoid this we will use this strategy instead:

- Check what time it is at the start of our game loop.

- Check what time it is at the end of our game loop.

- If more than 50 milliseconds have passed, immediately call the game loop function again.

- If less than 50 milliseconds have passed, use setTimeout, which lets us schedule a function to be called only once after a timer runs out.

Because we don’t schedule the next game loop until after we know the current game loop has finished we can now guarantee that we will never end up with multiple game loops interfering with each other. If a loop takes longer than 50 milliseconds we just wait for it finish before moving on. This will cause slight lag, but that’s better than having the engine actually break.

Now on to the nitty gritty technical details. When using setTimeout the first argument has to be a STRING copy of the code you want to run and the second argument is how many milliseconds the browser should wait before running it.

Making sure the first argument is a string is important. If the first argument is actual code it will be called immediately* instead of after the timer goes off. You can see this for yourself by experimenting with code like this:

//Wrong! The alert is called immediately

setTimeout(alert('Time Is Up!'), 2000);

//Right! The code inside the string gets called after two seconds

setTimeout("alert('Time Is Up!')", 2000);

The big risk here is creating infinite loops. For instance, our upcoming gameLoop function ends by scheduling another gameLoop. If you accidentally call gameLoop immediately instead of properly quoting it and scheduling it for later you will end up with an infinite loop of hyper-fast gameLoops instead of the steady one-loop-per-50-milliseconds you were hoping for. This will also probably freeze your browser. Happened to me. Don’t let it happen to you.

Prototyping The Loop

Open up the test code from two posts ago and replace whatever script you had with this:

var loopCount=0;

function canvasTest(){

gameLoop();

}

//The main game loop

function gameLoop(){

var startTime = Date.now();

getInput();

updateGame();

drawScreen();

var elapsedTime = Date.now()-startTime;

if(elapsedTime>=50){ //Code took too long, run again immediately

gameLoop();

}

else{ //Code didn't take long enough. Wait before running it again

setTimeout("gameLoop()",50-elapsedTime);

}

}

//Get the player's input

function getInput(){

//Empty prototype

}

//Update the game by one step

function updateGame(){

loopCount++;

}

//Draw the screen

function drawScreen(){

var canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

var context = canvas.getContext('2d');

//Draw background

context.fillStyle = '#dcdcdc';

context.fillRect(0,0,600,400);

//Draw black text

context.fillStyle = '#000000';

context.fillText("Loop Count: "+loopCount, 20, 20);

}

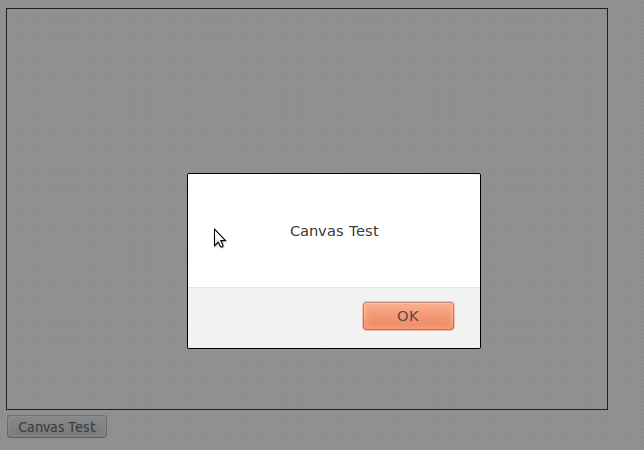

Now click the “Canvas Test” button and watch that counter climb at a speed of approximately 20 loops per second.

Let’s walk through the code really fast.

Clicking the button triggers canvasTest like usual, and canvasTest calls gameLoop.

gameLoop takes a note of what time it is (in milliseconds) by calling Date.now. The game loop then runs the three steps of our game (get player input, update game, and draw screen) and then checks how much time has passed by comparing the stored “startTime” to a second call to Date.now. If 50 or more milliseconds have passed we are running slow and need to call gameLoop again immediately. Otherwise we set a timer and have gameLoop run again later.

The three steps of the game are pretty empty at this point. We don’t care about player input so we leave that function blank. Our only game update is to increase the global “counterLoop” and painting the screen involves nothing but redrawing the background and printing a message about how many loops we have seen.

Next Time: Let’s Get Interactive

We’ve just built a simple but serviceable game engine skeleton. Now it’s time to start filling in the prototype functions, starting with getInput. Join me next week to see how that goes.

* There is one scenario where putting a function call in setTimeout would be a good idea: When the function’s main purpose is to return a string containing the code you actually want to schedule. Maybe you have a “builScheduledCode” function that returns different string wrapped functions depending on the state of the program. Like, if the debug flag is set it returns “logState();runLogic();” but if the debug flag is clear is only returns “runLogic()”;