Mom! He’s Touching Me!

Now that I think about it, none of my childhood family vacations ever involved the classic game of “How much can you invade your sibling’s personal space before they try to get you in trouble with Mom”. I feel deprived.

Anyways, this week’s topic is collision detection: the art of figuring out when two virtual objects are touching each other or overlapping. This is a very important element of game programming and really comes in handing when you need to know things like:

- Is the player standing on solid ground?

- Did the player just run into an enemy?

- Did the player just touch a power up?

- Is the player trying to walk through a wall?

- Did the player jump high enough to hit the ceiling?

- Did the player’s bullets hit an enemy?

Without collision detection a videogame would just be an interactive piece of art where you float around a world without physics watching things happen more or less at random. Which actually sounds kind of cool now that I think about it but that’s not what we’re aiming for right now.

Simple Collision Detection

We can’t detect if two objects are touching each other without two objects to touch. And no object is easier to work with than a rectangle which can be represented as a single x and y coordinate (representing the upper-left corner of the rectangle) along with a width and height.

//Sample Rectangle Code: Don't Put In Your Game

var testRect = new Object();

testRect.x = 5;

testRect.y = 20;

testRect.width = 10;

testRect.height = 30;

Now if we build two objects like this we can test if they are touching or not with this neat little math function, which is logically equal to this function from Wikipedia.

//Test if two rectangles intersect

//Arguments are two objects which much have x, y, width and height variables

function intersectRect(r1, r2) {

return !(r2.x > r1.x+r1.width ||

r2.x+r2.width < r1.x ||

r2.y > r1.y+r1.height ||

r2.y+r2.height < r1.y);

}

This function runs four quick tests that can each prove that the two rectangles ARE NOT touching each other. The first line tests if the second rectangle is too far right to touch the first rectangle. The second line tests if the second rectangle is too far left to touch the first rectangle. The third line tests if the second rectangle is too low to be touching the first rectangle and finally the fouth line tests if the first rectangle is too high up to be touching the first rectangle.

If all the tests fail then the second rectangle must be touching the first rectangle and the function overall returns true. Come up with a few samples and run the logic by hand if you like. It’s not like this articles going anywhere.

How Many Hitboxes Does One Character Need?

With that function we have everything we need to tell when rectangles collide. Now all we have to do is wrap all of our game graphics inside of invisible rectangles and it’ll be easy to tell when the player is running into enemies or crashing into platforms.

These invisible rectangles are called “hitboxes” and they are a vital game 2D* programming trick.

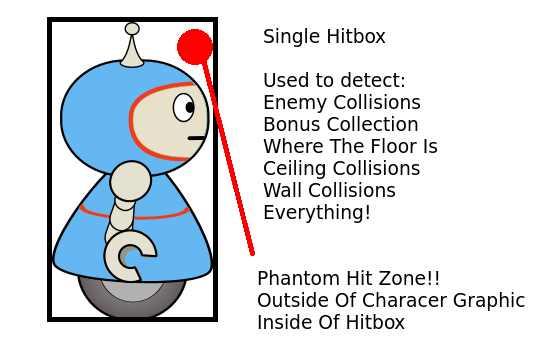

But there are certain problems with having your entire character represented by just one big hitbox.

For example: Imagine You detect that your one-hitbox character has run into a one-hitbox floating block. What happens next should depend on what direction the character hit the block from.

If they collided with the block from above they should land on the block and treat it like ground.

If they collided with the block from below they should stop moving upwards and instead start falling down.

If they collided with the block from the side they should stop moving and then slide downwards.

But since the character has just one big hit-box it’s really hard to figure out what kind of collision just happened. All you know is that the character and the block are touching; you don’t know where they are touching or what part of the character hit the block first.

There is also the big issue that giving a character one big hitbox usually creates a hitbox that is larger than the character’s graphics. This can lead to frustrating scenarios where the player winds up dead because an attack hit the blank space near his character’s head. It looks like it shouldn’t count as a hit but it’s inside of the invisible hitbox so it counts.

One Hitbox Per Character: Simple But Flawed

So one big hitbox makes it hard to tell exactly what is going on with your character and can lead to frustrating collisions for the player. This is a problem!

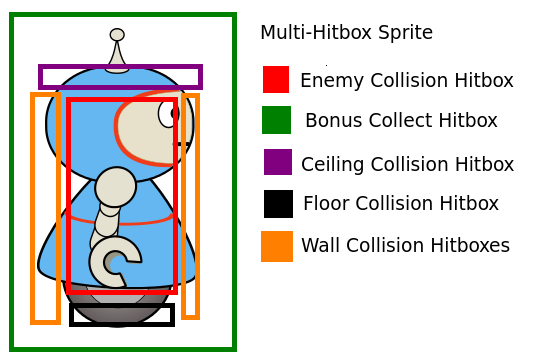

The simple solution is to give each character multiple hitboxes for different logic.

Some common hitbox types include:

Death box: A small, central hitbox for checking whether attacks hit the player or not. By making it smaller than the character graphics we give the player a little wiggle room and avoid the “phantom hits” we would get if the hitbox covered whitespace.

Bonus Box: A large hitbox that is used for detecting whether the player has touched bonus items or not. Slightly larger than the player so that they can grab coins and power ups just by getting really close without having to worry about exact pixels.

Feet Box: A short but wide hitbox used for detecting whether the player is touching the ground. We put it in the bottom center of the sprite.

Head Box: A short but wide hit box used for detecting whether the player has just bumped his head against the ceiling. We put it at the top center of the sprite.

Side Boxes: Two tall but thing hit boxes used for detecting whether the player has run into a solid obstacle. We put them on the left and right sides of the player.

Multiple Hitboxes: Much More Elegant

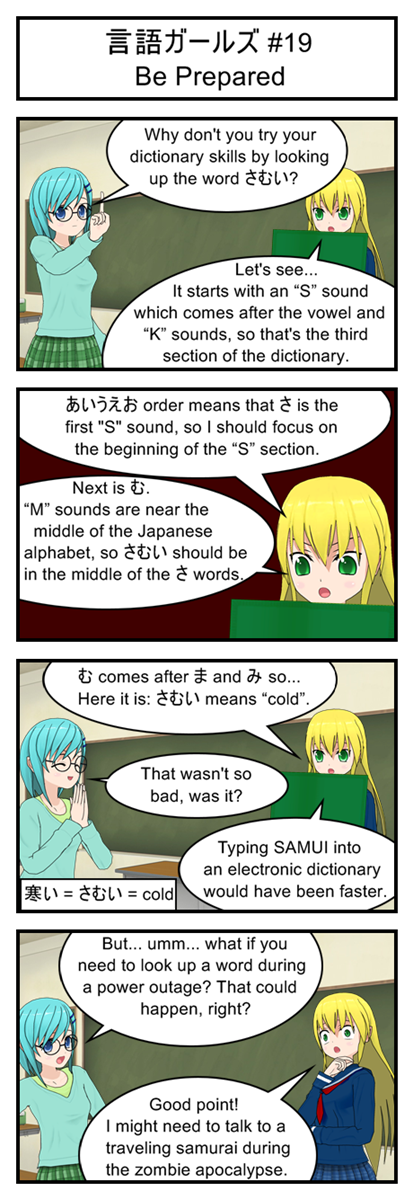

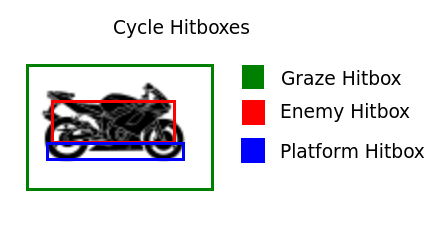

Hitboxes For Defrag Cycle

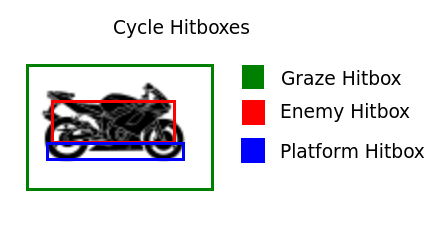

So how many of those common hitbox types doe we need for our game? Let’s see…

We need to be able to jump from platform to platform, so we’re going to need some sort of “foot hitbox” running along the bottom of the motorcycle.

We need to keep track of when the player runs into a virus and loses, so we’re going to need a small “death hitbox” in the center of the motorcycle.

We want to give players bonus points for grazing viruses, so we’re going to need a large “bonus hitbox” that’s actually a little bit bigger than the motorcyle. When a virus is inside this box but outside the “death hitbox” is when we give graze points.

We want players to be able to jump through platforms from below to land on top, so we DON’T need any sort of “head hitbox”.

The game has no walls, so we don’t need any “side hitboxes”.

So our final hitbox model for debug cycle has three hitboxes and will look something like this:

I think this should work

From Theory To Practice

Not a lot of code today, but that’s OK because we’ve laid down the groundwork we need to actually do some collision detection next time. Maybe throw is some gravity and get the player’s motorcycle to actually jump between platforms if I have the time.

* 3D games have a similar collision technique based around wrapping things with invisible cubes, cylinders and spheres.